Vancouver city’s emerging jewel in the Oakridge area will be boosted by the Jewish community’s $650-million decision to redevelop its 1.33-hectare regional centre on 41st Avenue.

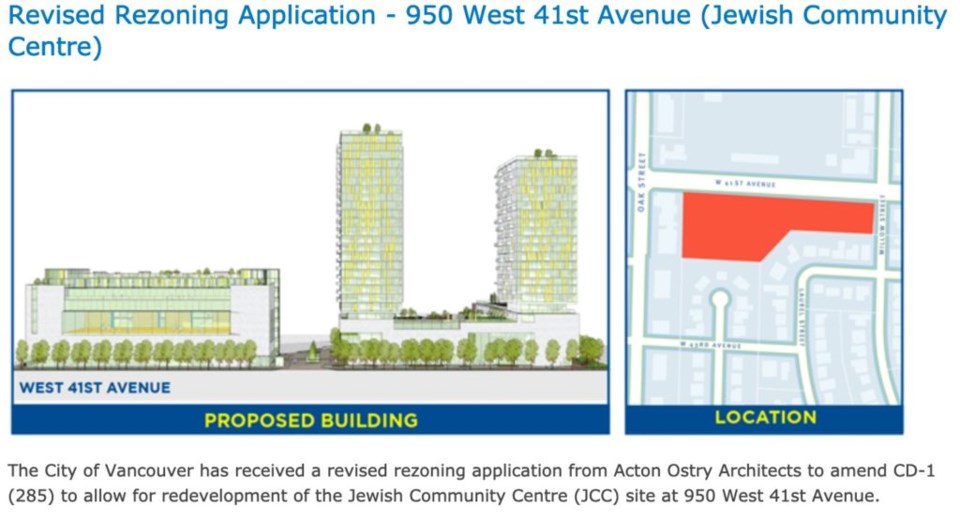

The Jewish Community Centre, which owns the property, and the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver, the community’s philanthropy and planning arm, have announced they will collaborate to build a complex comprising two tall towers and a podium on the 61-year-old site, part of the new Oakridge Municipal Town Centre.

With construction cost estimated at $350 million on a prime site that has approved zoning and development permits worth another $300 million, it will be the biggest project in the Jewish community’s 161-year history in British Columbia.

The complex’s 200,000 square foot of new space and smart technology-enabled, environmentally friendly facilities will also make it one of the largest and most modern among Jewish centres in North America, said two senior Jewish leaders for the Greater Vancouver region.

While primarily focused on looking after the region’s estimated 40,000 Jewish people, the new complex will continue to serve the wider and diverse communities in the city, said Eldad Goldfarb, the JCC executive director, and Ezra Shanken, chief executive of the Jewish Federation (JF) for Greater Vancouver in separate interviews.

The JCC remains Jewish and Canadian

The investment will both deepen the both the Jewish community’s roots in Oakridge, and its commitment to operate an inclusive place. Shanken sees it as a statement of the future of our community and Vancouver and “a beacon of hope.”

“We have people from different backgrounds interacting, and kids learning and playing together with each other at an early age,” he said.

“It is Jewish at heart and open to all,” said Goldfarb of the JCC’s mission statement, “even though it is called the Jewish Community Centre, membership is open to all.”

More than 30 percent of its 5,000 registered members are non-Jewish, mostly of Asian descent. Located near the Oakridge-41st Avenue Canada Line station, the centre attracts at least another 5,000 active users from Vancouver’s Jewish and other communities to its various programs throughout the year. That doesn’t include the high traffic of occasional visitors to popular events, such as the citywide annual film festival in which the JCC is an active participant.

“We have people from different backgrounds coming here for services, programs, theater, festivals and cultural activities. When you have that as part of your DNA at the JCC, it drives the planning policy right from the start,” said Goldfarb.

The site, bought from Canadian Pacific Rail in 1958 for $218,976, is currently home to a three-storey building and extensions nearing 60 years old, according to Acton Ostry Architects which is designing the new complex.

The effects of wear and tear are starting to show.

“We have increasing issues with maintenance, with replacement and repairs,” said Goldfarb, who has been heading the JCC since 2013.

What made redevelopment a slam-dunk decision is the JCC’s growing popularity, and the emergence of Oakridge as a hub along the increasingly dense Cambie Street corridor. The city has approved the construction of 32,000 new homes that will boost the corridor’s current population of about 35,000 to 85,000 by 2041.

Goldfarb described the challenges brought on by growth as “happy problems.” Shanken called them “opportunities” to be captured in one large capital project.

In managing the JCC, Goldfarb team has to juggle the competition for space among various groups both from within and outside the Jewish community:

“We are bursting at the seams,” he said.

The centre is home to 16 non-profit anchor tenants serving various aspects of Jewish life and programs linked to Israel, among them the JCC team itself, the Jewish Federation, the Holocaust education centre, the Canadian Friends of Hebrew University, Hebrew Free Loan Association, and the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs. The lack of space has limited their ability to expand or offer more services.

The JCC also operates programs for early childhood education and senior citizens that are working its facilities to capacity.

More than 200 children, Jewish and non-Jewish, attend pre-school, daycare and after-school care programs, with at least another 100 on the waiting list.

The JCC is also bracing for the impact of a rapidly aging population. Goldfarb said there has been a big increase in the new demographic of “young seniors” whose needs are vastly different from those of a generation ago. Mostly in their late 50s and early 60s, many are in good health and relatively well off, having retired at the end of successful careers.

“They don’t want to be treated as old people. They want to look young and to stay healthy,” said Goldfarb. This group wants more classes for yoga, dances, aquatics, and physical exercises.

The long journey ahead

The region’s relatively small Jewish community recognises the formidable task ahead to raise the $300 and $350 million Goldfarb estimates will be needed for redevelopment.

The first step has been taken with the JCC and Jewish Federation signing a memorandum of understanding transferring the property’s ownership to a new community entity and board of directors. The two organisations will jointly undertake fundraising activities as well as community and public consultations.

Calling it an historic project in the evolution of the local Jewish community, Jewish Federation chairperson Alex Cristall said the new JCC “will create a strong core that will ultimately allow us to increase our reach and our impact.”

The project will be undertaken in two phases, said Goldfarb, with the construction of the nine-storey podium for community and cultural activities taking precedence over the two towers that will have 299 rental housing units. The podium will include a swimming pool, gymnasiums, multi-purpose facilities, space for childcare and senior services, an expanded theatre, the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, and offices for the non-profit organizations.

There will also be commercial space for retail businesses. This presents a challenge as the podium for community activities is not designed to make a profit. That role falls on the rental housing component in the 24- and 26-storey towers expected to generate positive cashflow. About 60% of the apartments will be rented at market rates to subsidise the remaining 40% let out as social housing.

As a community organisation, Goldfarb explained, the JCC’s top priority is to ensure it continues to provide its full range of services during construction:

“We cannot shut down the JCC’s activities as that will leave 200 families and 500 seniors with no programs,” he said, adding that educational and cultural events for other groups would also be affected.

If this was a profit-driven project, the strategy would be straightforward: the developer would focus on building and selling the housing units first. The sale would immediately generate a positive cashflow to enable the developer to secure financing. But Goldfarb makes it clear that the Jewish community will not sell any of the units as part of its fundraising strategy.

“The plan is to keep the land and the assets in the hands of the community. Forever,” he said.“This is not another piece of land in Vancouver to be speculated on and traded for a profit. We are a charity, not a profit company.”

He said the podium’s construction, estimated at around $150 million, will be funded by a combination of donations, community financing, and government support. The group is also exploring the idea of offering a bond directly linked to the project that will pay investors a yield until maturity.

“This will appeal to investors who want to subscribe and to earn a return. That would enable us to get funding upfront,” said Goldfarb.

At around $200 million, the complex’s housing component is more costly than the podium, but its financing will be more straightforward and probably easier to raise. Goldfarb said the group will be working with government authorities such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and BC Housing who can provide financing as part of their mandate to tackle Vancouver’s dire need for rental housing.

The Vision

If everything goes completely to plan, Goldfarb said the JCC would have a gleaming new complex in 2026 – but almost as quickly, he added: “we should factor in delays and budget issues.”

The cautionary tone suggests a seven-year time frame is probably too ambitious, not unusual given a project of this size and complexity.

Nevertheless, Goldfarb did not flinch from giving a bold target within a broad timeline. Planning for the whole complex, raising funds, and building the podium’s community centre would take up to five years. After that, work on the two towers should be completed within two years, he estimated. It helps that there are no plans for an underground carpark; excavation work would take up between six months and a year.

A major feature of the new complex is security – a crucial consideration amid rising incidents of hate crimes in Canada and around the world, with the Jewish community often a key target. According to the Vancouver Courier citing Statistics Canada, Metro Vancouver has the highest rate of hate crimes among Canada’s main regions.

At the same time, the planners will endeavour to minimise security becoming a barrier to entry for members and users. “We have to make this the most secure and yet welcoming building,” said Goldfarb.How about smart features? Of course.“That’s what the city council asked as well. They also asked about green features like a food digester, renewable energy facilities, etc. The building will have the features to match the times.

“We have to think about how the new building has to be environmentally friendly, how it can be scalable and flexible, and how it can be secure.”

When completed, the complex’s most important feature will not be its technology, modernity, or aesthetics, but the continuation of the Jewish role in the Canadian identity built on its diverse, vibrant communities.

Ng Weng Hoong is a veteran reporter with over 30 years of experience covering the energy industry mostly in Asia. These days, Ng watches the world from his Vancouver apartment. His focus is increasingly on China, its impact on the Chinese diaspora, and the complex relationships that they have with each other and other countries.

SWIM ON:

- BC also has Canada's oldest surviving and operating synagogue, Temple Emanu-El in Victoria. May Q. Wong looked back at its founding.

- Previously, Ng Weng Hoong looked at BC's burgeoning LNG industry and the role in could play in Canada's relations with China.

- "If I was starting a business now, it wouldn't be in Vancouver." Ada Slivinski on the astronomical property taxes levied on small business in BC's biggest city.