In Part II, I highlighted how Britain had largely negotiated the acquisition of Rupert’s Land to Canada without making any explicit directive to extinguish Aboriginal title, which was largely concurrent with British Columbia’s own union with Canada.

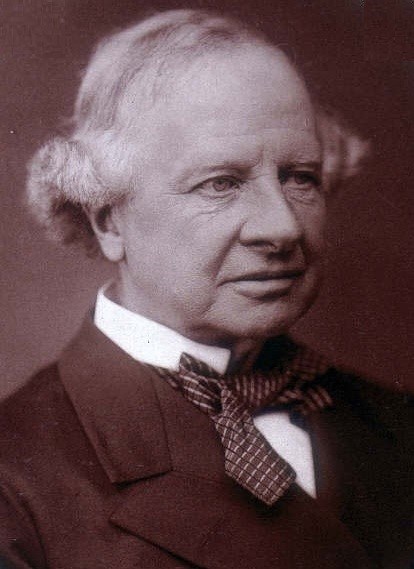

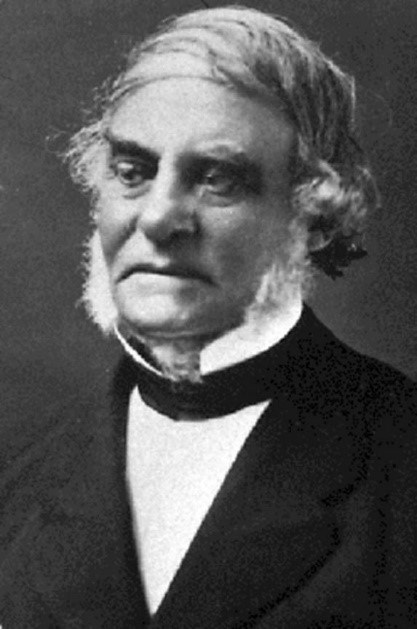

Lord Granville, secretary of state for the colonies, viewed the Rupert’s Land Order (which he personally negotiated) in a largely undefined way with regard to Native peoples, and consistent with previous imperial policy. Welfare and protection of Indigenous peoples was guaranteed, but no explicit directive issued. Writing to the governor general of Canada, John Young, 10 April 1869, he stated:

I am sure that your Government will not forget the care which is due to those who must soon be exposed to new dangers, and, in the course of settlement, be dispossessed of the lands which they used to enjoy as their own, or be confined within unwontedly narrow limits. This question had not escaped my notice while framing the proposals which I laid before the Canadian Delegates and the Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. I did not, however, then allude to it, because I felt the difficulty of insisting on any definite conditions without the possibility of foreseeing the circumstances under which these conditions would be applied, and because it appeared to me wiser and more expedient to rely on the sense of duty and responsibility belonging to the Government and people of such a country as Canada.

With Canada’s acceptance of the Rupert’s Land transfer agreement they effectively adhered to Britain’s direction and dropped any reference to Native rights or compensation. The Canadian Parliament resolved “That upon transference of the territories in question to the Canadian government, it will be the duty of the Government to make adequate provision for the protection of the Indian tribes whose Interests and well-being are involved in the transfer.”

Nonetheless, Canada subsequently ratified a treaty with the Chippewa and Swampy Cree Tribes, 3 August 1871, at Lower Fort Garry (Manitoba) where compensation was paid “as a present of three dollars for each Indian man, Woman and child belonging to the bands” and then further annual payments of $15 per family of five.

This was, it seems, the start of a uniform Canadian policy that – independent of clear imperial direction – advanced treaty payments to maintain peaceful relations.

While Lord Granville oversaw applications of Canadian native policy to what would become western Canada, he also used his influence to urge the Colony of British Columbia towards union. It is important to remember that Indigenous policies, whether in Canada or Rupert’s Land, were at the forefront of Canadian politics during the British Columbia confederation debates. In fact, the BC debates of union with Canada were approximately simultaneous with the transfer of Rupert’s Land (1869), the creation of the Province of Manitoba (1870), and the Lower Fort Garry Treaty (1871).

Lord Granville subsequently wrote to the last governor of British Columbia, Anthony Musgrave, 14 August 1869 (while the Rupert’s Land negotiations were being finalized), that it was time for British Columbia to give fuller consideration to union with Canada.

The question, therefore, presents itself whether this single Colony should be excluded from the great body politic which is thus forming itself. On this question the Colony itself does not appear to be unanimous. But as far as I can judge . . . . I should conjecture that the prevailing opinion was in favour of union. I have no hesitation in stating that such is also the opinion of Her Majesty’s Government . . . . The constitutional connexion of Her Majesty’s Government with the Colony of British Columbia is, as yet, closer than any other part of North America; and they are bound, on an occasion like the present, to give, for the consideration of the community and the guidance of Her Majesty’s servants, a more unreserved expression of their wishes and judgement than might be elsewhere fitting . . . . It will not escape you, that in acquainting you with the general views of the Government, I have avoided all matters of detail, on which the wishes of the people and the Legislature will of course be declared in due time.

I think it necessary, however, to observe that the constitution of British Columbia will oblige the Governor to enter personally on many questions – as the condition of Indian tribes and the future position of Government servants, with which, in the case of a negotiation between two Responsible Governments, he would not be bound to concern himself.

The Granville letter contain three important considerations. Firstly, BC had not achieved responsible government and, therefore, the imperial government was required to act on their behalf in framing the Terms of Union with Canada, as Granville had done with Rupert’s Land.

Secondly, with respect to “the conditions of the Indian tribes,” Granville (in consultation with Governor Musgrave), played the central role as negotiator in lieu of the BC Legislative Council.

Thirdly, the letter highlights Granville’s acknowledgement that he was well-acquainted with the BC despatches that had reached him, and was obviously well-apprised on British Columbia matters. This is worth stressing in that one of the despatches detailed the conditions of Indigenous peoples in BC. The memorandum prepared by Joseph Trutch was also included with this despatch and stated that “the title of Indians in the fee of the public lands, or any portion thereof, has never been acknowledge by Government, but, on the contrary, is distinctly denied.”

Lord Granville was the central figure in all negotiations with regard to native peoples in both BC or Rupert’s Land. In both instances Granville reserved the right to imprint and enshrine native policy according to rather loose imperial standards. Even though Joseph Trutch confirmed that aboriginal title was “distinctly denied” by British Columbia, no objections were forthcoming from the secretary of state for the colonies while negotiations were underway. It can be argued BC was not out-of-step with the imperial policy of the time.

Governor Musgrave subsequently conveyed Granville’s pivotal role in any confederation negotiations to the BC Legislative. “Any arrangements which may be regarded as proper by Her Majesty’s Government,” wrote Musgrave, “can I think best be settled by the Secretary of State, or by me under his direction, with the Government of Canada.” Yet, certain members of the BC Legislative Council were anxious that the application of the Canadian native policy to BC would adversely affect both Indigenous peoples and the colony’s economy.

Henry Holbrook – the main advocate of entrenching native welfare and protection within the BC Terms of Union – spoke of native peoples residing in his riding of New Westminster.

“The Indians of the Lower Fraser are intelligent, good settlers,” asserted Holbrook, and “I ask that they receive the same protection under confederation as now.”

Thomas Humphreys echoed the notions of welfare and protection:

“Take away the Indians of New Westminster, Lillooet, Lytton, Clinton, [stated Humphreys] and these towns would be nowhere. I say the Indians are not treated fairly by us, and all they want is fair dealing from the white population. . . . I say, send them out to reservations and you destroy trade, and if the Indians are driven out we had all best go too.”

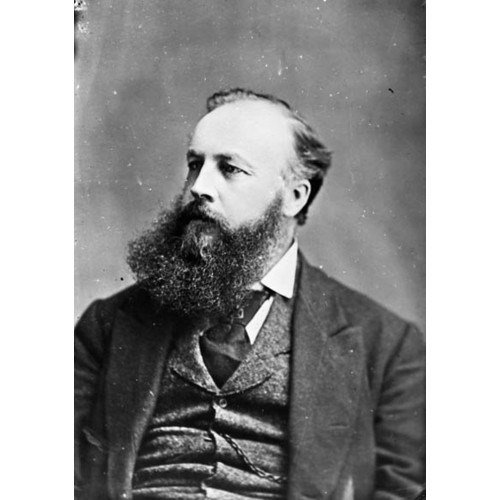

Dr. John S. Helmcken agreed. “I think it right to get the best terms we can, and point out the difficulties,” he stated. “I say if the Indians are to be stuck in reservations there will be a disturbance. I think, sir, that it will be well that there should be some opposition.”

Years later, in 1887, Helmcken (who had represented BC in the confederation negotiations) expanded upon this view:

“It was the ‘policy’ of the Govt. of Vancouver Island not to remove any tribe or family from their village sites – but to make reserves of land immediately around and including their habitations. The Indians to-day occupy the same sites they did when I first arrived in 1850. None have ever been removed and so by the same token have never been removed to ‘reserves’, using this term in the Canadian or American sense. It was never intended that the Indians should be a separated community . . . . It must therefore be evident that the Indian policy of Vancouver Island differed altogether from that of Canada. In fact it was knowingly framed seeing the great disadvantages of that system.”

These members of the BC legislative council expressed a view that the Canadian system would serve to banish natives to distant reserves, pay them annuities, and prevent their active involvement in the BC economy. This impression seems correct; in later years Indian reserves in the Prairie provinces followed this model of relocation, in addition to not being allowed outside reserve boundaries without obtaining a pass from the Indian agent (following the Northwest Rebellion).

Holbrook’s motion to enshrine protection of native peoples in the Terms of Union failed (20-1), not because of the intent of the motion, but because it conflicted with Lord Granville’s directive that omitted any participation by the BC Legislative Council on native questions. As noted earlier, like Article 7 (Tariffs), responsibility for Indigenous peoples was within sole federal jurisdiction.

Henry Crease, the colony’s attorney-general, bolstered this view when he stated that “The honorable gentleman must have forgotten the direction of the Imperial Government.” Other members agreed. “We have the full assurance in Lord Granville’s despatch that Indians must be protected,” stated Dr. Robert Carrall (who, along with Helmcken would represent BC in Ottawa during the confederation negotiations).

At the conclusion of the confederation debates, a draft Terms of Union was ratified by members of the BC legislative Council that included no specific article governing native peoples. Article 13 was inserted into the final terms after BC delegates had negotiated directly with the Canadian government in Ottawa. Article 13 stipulated that:

The charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit, shall be assumed by the Dominion Government, and a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government, shall be continued by the Dominion Government after the Union.

To carry out such policy, tract of land of such extent as it has hitherto been the practice of the British Columbia Government to appropriate for that purpose, shall from time to time be conveyed by the local Government to the Dominion Government in trust for the use and benefit of the Indians on application of the Dominion Government; and in case of disagreement between the two Governments respecting the quantity of such tracts of land to be so granted, the matter will be referred for decision of the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

The Article 13 phrase stating “a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government” did not suggest that native land management policy in BC was similar to (or more advantageous than) Canadian policy. Many have interpreted the use of the word “liberal” as British Columbia’s way of hiding the true nature of the BC native policy. It has also been suggested that had the Canadian government fully known the BC position, such wording would not have been agreed to. But this is not the case.

The “liberal policy” guaranteed that Indigenous peoples were not to be isolated onto reserves and prevented from continuing as active participants in the BC economy. The word liberal speaks of “liberty of action” as promised by Governor James Douglas to Indigenous nations in the aftermath of the Fraser River War of 1858, and the guarantee that that BC native peoples would not be relocated from traditional lands.

It is also unlikely that Article 13 can be attributed to Joseph Trutch, as many have suggested. Though Trutch was one of three delegates (along with Doctors J.S. Helmcken and R.W.W. Carrall) appointed to negotiate the terms of confederation, Lord Granville and George Cartier are the likely authors. Granville had defined his exclusive role with respect to BC natives (precluding BC legislative council participation). George Cartier, senior Canadian negotiator in determining BC’s Terms of Union (in addition to the elevation of Manitoba to provincial status), had also represented Canada in the Rupert’s Land transfer with Granville that included guaranteeing welfare and protection for native peoples.

The confederation diary of Dr. Helmcken stated “The clause about Indians was very fully discussed. The Ministers thought our system better than theirs in some respects, but what system would be adopted remained for the future to determine.”

As with Article 7 (Tariffs) and 11 (Railways), Article 13 was left to future governments to clarify. As Cartier subsequently stated to the Canadian House of Commons, “the only guarantee that was necessary for the future good treatment of the Aborigines was the manner in which they had been treated in the past.”

Canada, like the imperial government, had knowledge of the BC position both before, during, and after the Terms of Union were ratified – and like Articles 7 and 11, a potentially divisive issue was left unresolved in order to secure union with Canada.

As for Indigenous peoples in BC, the British government was complicit in having claimed the sole authority to negotiate on behalf of the Crown Colony of British Columbia.

In doing so, it effectively side-stepped the issue of Indigenous title that continues to claim the BC landscape today.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Get caught up on Part 1 and Part 2 of Daniel Marshall's series on BC's negotiations with Canada to enter Confederation.

- For (much) more recent history, check out Daniel Fontaine on Vancouver's 2010 Olympics.

- The more things changed, the more they stay the same. As Doug Firby reports, provincial trade barriers are still very much an issue today.