On August 25th, 2018, we launched our 160th Anniversary Raft Expedition from Boston Bar to Yale to commemorate the 1858 Fraser River Gold Rush & Canyon War.

Running the river through Hell's Gate and the Big Canyon was thrilling good fun, and the chance to re-imagine the events leading to the largely unexplored native-newcomer conflict of 1858, which resulted from the rapid influx of some 30,000-plus foreign gold seekers into the New El Dorado of the North.

Or, what would become British Columbia.

On August 16th 1858, thousands of gold seekers gathered in Yale, and elected their officers to command miner-militias to confront Indigenous populations that had blockaded the Fraser River (it was Indigenous peoples who were the discoverers of gold in B.C., and actively mined before the gold rush commenced).

One such militia was commanded by Captain Henry Snyder, a well-known San Franciscan, whose plan was to make peace with First Nations. Snyder led the Pike Guards on a 10-day military-like campaign from Yale to Kumsheen (today's Lytton), but not before encountering an opposing militia at Spuzzum, led by Captain Graham of the Whatcom Guards.

Graham and his party were bent on exterminating all Indigenous peoples they might encounter. In a letter to Governor James Douglas, Snyder reported:

“They wished to proceed and kill every man, woman & child they saw that had Indian blood in them. To such an arrangement I could not consent to. My heart revolted at the idea of killing a helpless woman, or an innocent child was too horrible to think of.”

Snyder demanded Graham stand down and let him broker a peace. If successful, a white flag would be sent through the Big Canyon to let him know that his mission was successful.

Soon after Snyder left Spuzzum, the Whatcom Guards were on the move again. Snyder sent runners back to plead once more to stay put, and that if he did not, Snyder would end his peace mission and head back to Yale immediately. Graham, once again, agreed to wait.

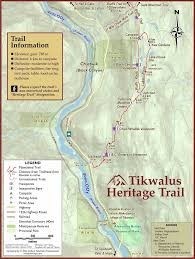

As Snyder and the Pike Guards climbed the steep, ancient Tikwalus Trail from the vicinity of Alexandra Lodge, the Whatcom Guards made camp “on a large shelving rock” opposite the vicinity of Chapman’s Bar, and placed sentries at either end for protection.

Snyder ultimately descended the Anderson River to Boston Bar, continuing to make treaties of peace with Native villages along the way, and as promised, sent a white flag down through the Big Canyon to Graham as evidence of his success.

Upon receiving the flag, Graham reportedly ordered it tossed aside, presumably upset that his campaign of extermination had been thwarted.

That night, pandemonium ensued.

Captain Graham and his first lieutenant were both shot dead, apparently by Indigenous peoples who had seen the treatment given to the white flag of peace.

Snyder reported, “Had he done as he promised to do, he would now be alive.”

I have always wondered where exactly the leadership of the Whatcom Guards and their extermination campaign met their end, 160 years ago this summer.

Sitting one day at a pull-off on the TransCanada Highway, I again looked down on the river corridor (see above). I could clearly see Chapman's Bar on the left side of river – “bar” was California parlance for a sand & gravel bar. I could also see the "large shelving rock" -- a substantial rock point jutting into the river on the right.

It seemed to me that our Raft Expedition would be a grand opportunity to visit this site.

Strategically, it made sense. As I stood atop this rock promontory I immediately saw that it was the best place to post sentries, who could see clearly all the way up and down the river.

It was the most strategic point on the river for military defense.

The Tikwalus Trail (on the left side of river), now restored as the Tikwalus Heritage Trail, is very steep for the first two kilometers. I imagined Snyder looking directly down and right across Chapman's Bar to the "large shelving rock" that fateful day.

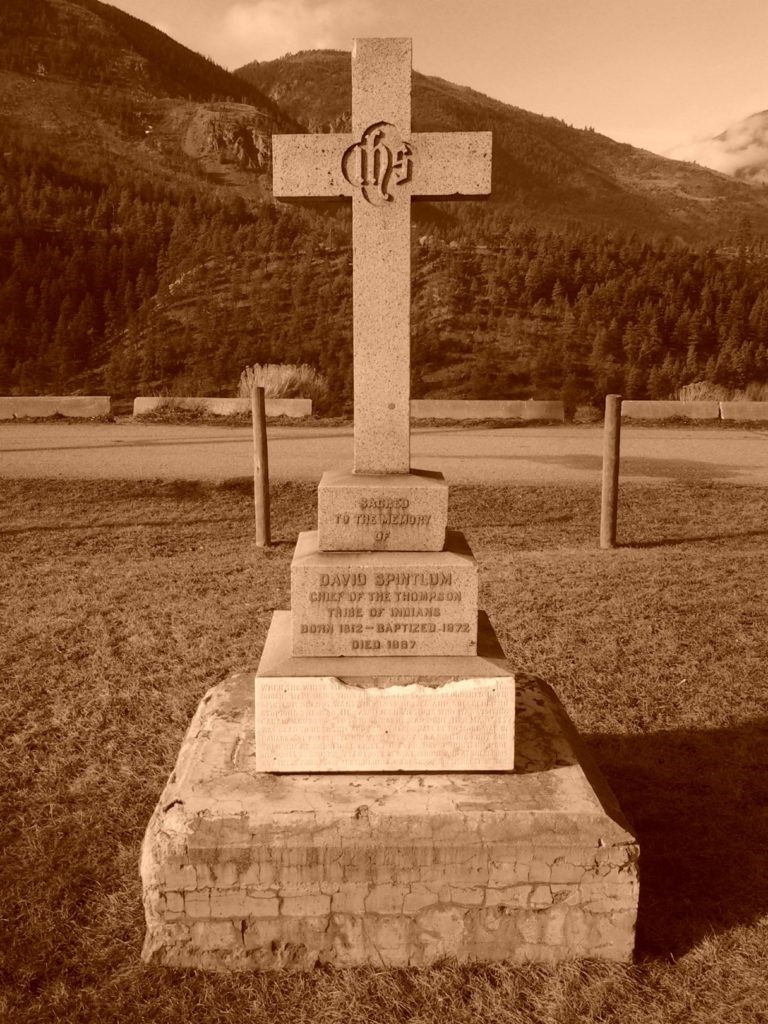

Below him were gold seekers clamoring for outright extermination of Indigenous peoples. Above in Lytton, waited the great Chief Spintlum of the Nlaka’pamux Nation for their "grand council of war" in which, quite miraculously, peace was achieved.

I firmly believe that we were standing on the general location of the Whatcom Guards' camp ground.

Here, the worst aspect of the California mining frontier ("a good Indian is a dead Indian") was halted in its tracks, the leadership of the Whatcom Guards effectively decapitated, not unlike the headless bodies of foreign miners found drifting down the mighty Fraser River 160 years ago this last summer.

Here, a Californian and a Native Chief chose peace – the great untold story of B.C.’s founding.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.